Getting Off the Crack

/For a long time, I relished the way I could “crack” my back and neck. Just the right turn of my torso would send a ripple of clicks and releases along my spine. My idea about it was that those cracks were “unsticking” the gears of my body-machine. But there was also an underlying pattern playing itself out. Those cracks were a symbol of sorts, they represented all the breakthroughs and “tapas” I had accomplished through my many years of diligent practice. The cracks felt good, at least until they didn’t anymore.

My early instructors all emphasized lengthening and opening as ultimate expression of the physical work. The more flexibility and extension I could demonstrate through intricate body shapes, the more respect and praise I received for being a serious practitioner. No one ever talked about function. Regardless of whether the focus was on alignment or sequence, it was always about the form. Those equipped to execute the most revered forms were given a leg-up compared to those who only aspired to as much.

What I always thought of as “opening” was really just me pulling my body apart.

As the years went on, all that lengthening and opening resulted in a range of chronic pains and degenerative issues. I was fortunate to find my way to different approaches that de-emphasized the physical work as a goal, focusing more on utilizing simple forms for nurturing and healing. This shift of purpose was profoundly helpful in addressing many of my unconscious motivations and forging new protocols that better served my intentions. But even after turning that corner and establishing a change in my direction, I’ve still hung on to those cracks.

Despite fully embracing a simpler practice, based on non-achievement, the lens with which I perceive a useful end-range for my body, and my notions about functionality, remain deeply clouded by idealized images and ingrained patterns. It’s hard to know or trust what you feel to be true if you are too busy trying to impress or receive approval from others. And the demands of maintaining a practice that also doubles as a profession add further complications to addressing what is a densely layered and personal matter.

Hitting the bottom of my addiction to cracking my back has had larger implications on my practice and teaching.

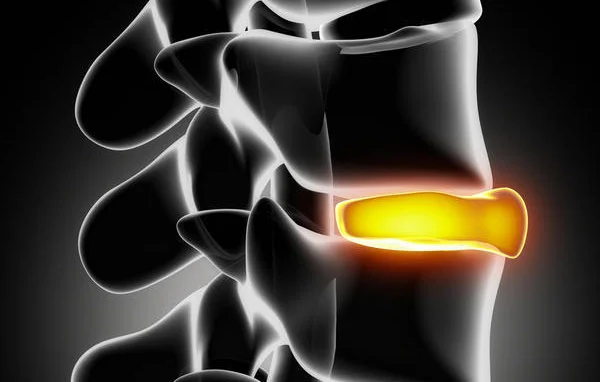

Pain has a funny way of changing your mind about things. It has become impossible for me to deny that the areas where my pain seems to originate, or often is most localized, are exactly the places where I usually get my best cracks. And when the pain becomes more pronounced, and the cracks no longer give any relief, I am forced to admit to myself that all that cracking over the years was maybe not such a good idea.

Too many instructions readily offered on how to hold our bodies or do poses are either profoundly misleading or outright falsehoods. Many of these standard cues are deeply burned into us. Taking my shoulders up and back no longer feels like a good choice. In fact, letting them roll a bit forward, which after so many years of pulling them back makes me feel like I am the Hunchback of Notre Dame, both feels and looks better. Who decided that it was a good idea for us to do that with our shoulders as a default setting for “good” posture? The time has come where yoga teachers can no longer continue to assert ideas about the human body without also being able to coherently explain how they know what they know.

In a post-lineage age, rampant with reductionist science, new models must be developed on the pillars of process and transparency.

Hunched-over shoulders is often considered an expression of protection or “shutting down” from our experience. In my role as a yoga teacher, my defense mechanism has been to portray the physical opposite of that. I’m the one in the front of the room with my shoulders back, who can sit up taller and longer than everyone else, and is charged with helping us all be better. The burden of holding myself up as that example was me doing my job as best as I knew how. But ironically, attempting to express openness through an exaggerated physicality, and a mythologized idea of posture, can equally be indicative of guarded vulnerability or trauma.

You see, all the sitting up as straight as I can all the time, and keeping my shoulders back so my heart is open, were also undoing some of what my body needs to be well over time. My thoracic spine wants to have a curve, and my shoulders are an inefficient starting point by which to hold myself upright. So, I think it’s time to let go of that stuff. No more intentional back or neck cracks. That idea about my body is done, and I am already feeling better.

This post is largely inspired by the work of Amy Matthews. I highly recommend checking her out. And thanks to Theo Wildcroft for coining the term 'post-lineage.'